This is about a very early detective, though not actually a private detective in the modern sense. He wasn’t a policeman either: They did not exist in the 15th Century, certainly not as we know them today. However, Sir Guillaume de Tignonville could be described either as the King’s private detective or as a public official. Despite his English-sounding title, he was the Provost of Paris, the chief law enforcement officer responsible to the King of France and through the authority of the King, to the people of that country.

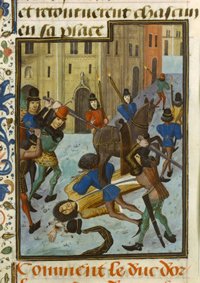

One night in November 1407, de Tignonville was called out to the scene of a horrific murder. The victim, Duke Louis of Orleans, was none other than the brother of King Charles VI. Duke Louis ruled as Regent when necessary, the King himself sadly being insane. Poor Louis had been hacked to death by a group of masked assassins who had fled the scene.

De Tignonville was tasked with tracking down the murderers and bringing them to justice. He was not, by training or experience, a detective. He was a knight, a fighting man and campaign veteran, but he was also a man learned and experienced in law. He set about his investigation in a manner which puts him centuries ahead of his time.

Making full and effective use of the manpower made available to him, de Tignonville methodically searched out witnesses, established their veracity, had statements and depositions taken and gradually built the picture of what had happened. He and his assistants meticulously examined the scene of the crime and gathered physical evidence in support of the verbal evidence being collected.

Eventually, the evidence trail led de Tignonville to some of the highest levels of French society. It must have taken great courage on his part to demand access to the chateaux and palaces of the mighty in order to search for evidence of complicity in the conspiracy to which his enquiries had led him. However persistence paid off, leading to a confession from no less a personage than a member of the Royal Family.

No forced confessions or statements: None of the torture or other brutality common at that time; just diligent detective work, legwork and persistence. How do we know all this? Another pioneering aspect of de Tignonville’s methodical approach: Everything was meticulously recorded in writing using quill pens.

The record filled a scroll thirty feet long! It somehow vanished not long after it was completed and didn’t reappear for three hundred years. Then it was stored away in the Royal library in Paris and forgotten about for nearly another hundred years’ Then in the mid 19th Century it was discovered and eventually printed and published.